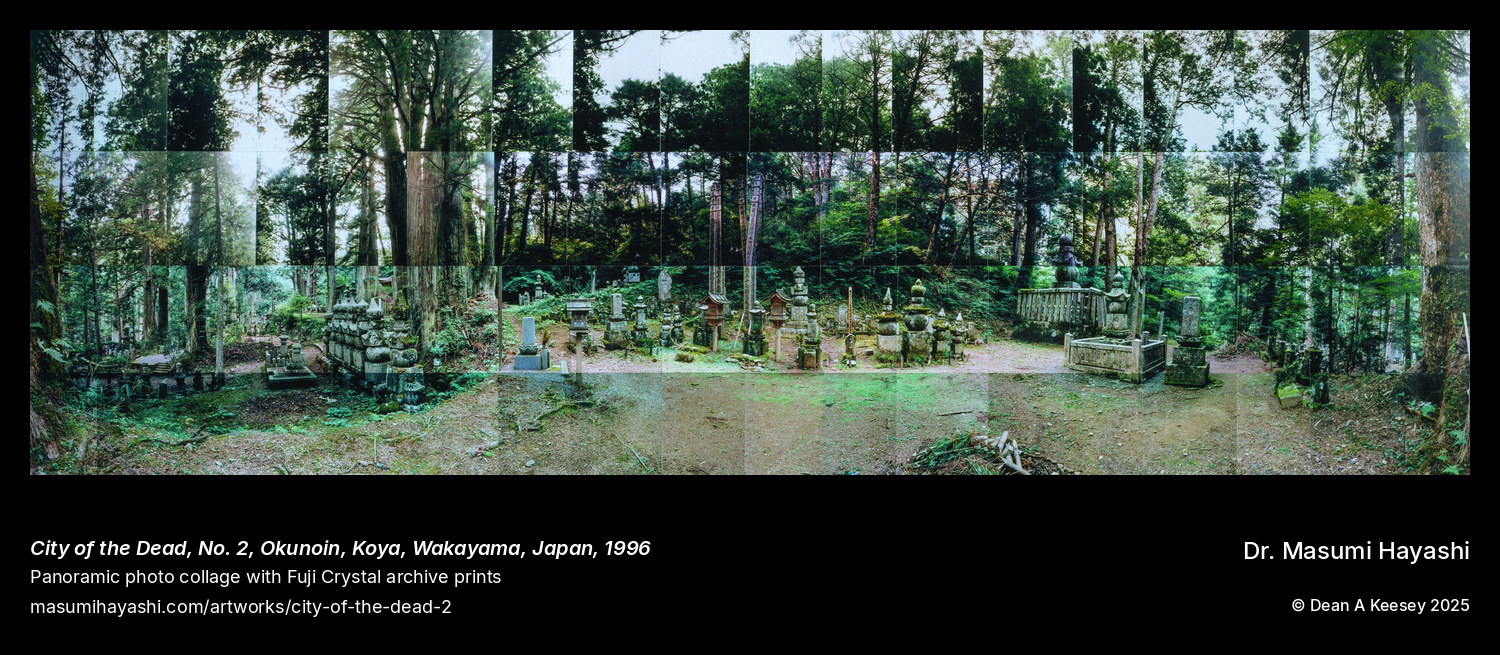

City of the Dead, No. 2, Okunoin, Koya, Wakayama, Japan

Okunoin, Koyasan, Japan

Panoramic Photo Collage

1996

17 x 53

The second Okunoin work (identical 17-by-53-inch dimensions) captures what the first couldn’t: different light filtering through canopy, alternative perspective along the two-kilometer path, complementary view of how 1,200 years of continuous burial creates vertical architecture from horizontal death. Both pieces share extreme narrowness—53 inches tall, just 17 inches wide—the second-narrowest format in Hayashi’s entire output. The repetition suggests deliberate strategy: this cemetery demands paired documentation, different vantage points revealing complexity single images can’t contain.

Walking Okunoin means descending through temporal layers. The path begins in areas where feudal lords and samurai established memorials—stone markers recording warrior lineages, monuments to violence seeking posthumous redemption through proximity to Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum. Deeper in, older sections reveal weathered wooden markers where legibility fails, names consumed by moss and rot, identity surrendered to forest encroachment. Then modern corporate memorials appear—companies honoring deceased employees through geometric stupas bearing company logos, 21st-century capitalism adapting Buddhist memorial tradition to organizational identity. The Torodo Lantern Hall glows with thousands of offerings. Finally, the inner sanctuary where monks maintain daily food delivery to a saint who entered “eternal meditation” in 835 CE and reportedly requires feeding still.

The paired vertical formats capture what horizontal panoramas cannot: how cryptomeria cedars tower overhead creating cathedral darkness, how five-element gorinto stupas stack representing earth-water-fire-wind-void, how the path narrows between monuments closing lateral sight lines until only forward and upward remain as visual options. The constricted 17-inch width isn’t limitation; it’s accurate phenomenology of walking this compressed space where 200,000 graves compete for proximity to the mausoleum’s salvific presence. Horizontal formats would misrepresent the experience. This is vertical landscape: ascending trees, stacked memorial elements, depth perspective descending through monument density toward inner sanctuary.

The two-work strategy establishes documentation pattern Hayashi later employs at major sites. Airavatesvara Temple receives horizontal and vertical pair capturing different architectural elements. Meenakshi Temple earns multiple perspectives exploring labyrinthine complexity. Angkor Wat gets numbered sequence (No. 1 confirmed, additional works likely) acknowledging that monuments this significant can’t be reduced to single representative images. Serial documentation honors complexity, admits that comprehensive understanding requires multiple approaches, different compositional strategies, varied perspectives along pilgrimage routes.

As 1996 works, these Okunoin pieces predate Hayashi’s major India-Cambodia-Nepal journey (2000-2004) by four years, establishing Japanese Buddhist death culture as foundational Sacred Architectures theme. While later temple documentation emphasizes living devotional practice and architectural monumentality, these cemetery works explore different sacred topology: how landscape organizes around death, how forest architecture emerges from burial density, how wabi-sabi aesthetics celebrating impermanence coexist with miracle claims about undying saints. UNESCO designated Mount Koya World Heritage in 2004, recognizing Shingon Buddhism headquarters. But Okunoin’s power derives from living tradition specific enough to require daily food delivery, from belief that burial location affects posthumous trajectory, from 1,200 years of accumulated conviction that proximity to one meditating saint transforms death from terminus to opportunity. When Hayashi photographed these moss-covered monuments beneath ancient cedars, she documented sacred landscape where every stone argues with mortality, where forest reclaims everything except the claim that matters most: that deep in the inner sanctuary, Kobo Daishi still waits, still watches, still protects those who chose to rest their bones near his.