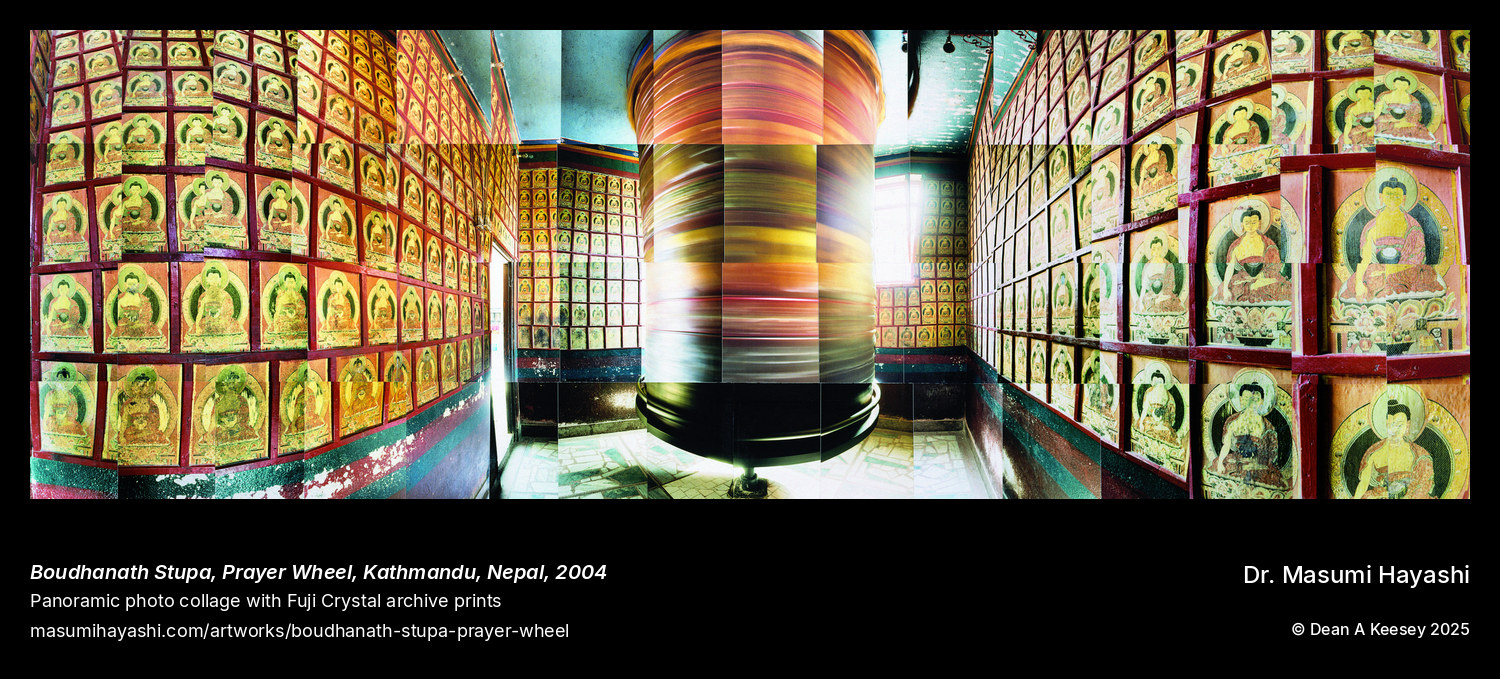

Boudhanath Stupa, Prayer Wheel, Kathmandu, Nepal

Kathmandu, Nepal

Panoramic Photo Collage

2004

56" x 19"

In 2004, Hayashi photographed Buddhist technology—cylindrical metal wheels mounted on spindles around Boudhanath Stupa’s base, each containing tightly wound scrolls inscribed with thousands of “Om Mani Padme Hum” mantras. Tibetan Buddhist tradition holds that spinning these wheels generates merit equivalent to vocally reciting all contained prayers, amplifying devotional practice through mechanical means. Pilgrims walk clockwise around the massive white dome, spinning each successive wheel with their right hand, coordinating physical movement, manual rotation, verbal recitation, and meditative focus into unified practice integrating body, speech, and mind. The wheels create visual rhythm along the circumambulation path, their metallic surfaces catching sunlight, their constant rotation by successive pilgrims generating shimmer and the distinctive clacking, whirring, creaking sound of devotional mechanics.

Boudhanath’s significance transformed in 1959 when Chinese military occupation of Tibet sent thousands of refugees fleeing across Himalayan passes into Nepal. What had been primarily a Newar Buddhist pilgrimage site became the world’s most significant Tibetan Buddhist center outside Tibet itself. Refugees established dozens of monasteries representing major lineages—Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, Gelug—creating thriving exile community infrastructure around the ancient stupa. By 2004, shops sold prayer wheels, thankas, ritual implements; restaurants served Tibetan cuisine; guesthouses accommodated pilgrims; Western Buddhist practitioners studied with Tibetan teachers in meditation halls and retreat centers. The massive mandala structure—approximately 36 meters tall with distinctive Buddha eyes painted on four sides gazing in cardinal directions—presided over complex social and religious landscape where traditional Newar communities, Tibetan refugees, and international practitioners shared sacred geography while bringing different cultural approaches to circumambulation practice.

The extreme horizontal format—56 by 19 inches, among the widest in Hayashi’s Sacred Architectures series—documents lateral movement rather than vertical monumentality. This isn’t architectural study emphasizing the stupa’s soaring dome and gilded spire. It’s documentation of living practice, of continuous devotional activity, of how sacred architecture generates human movement and ritual choreography. The 56-inch width potentially encompasses substantial portions of the circumambulation path, multiple pilgrims at different stages of their clockwise journey, the sequential rhythm of prayer wheels spaced along the base. The relatively compressed 19-inch height maintains focus on ground-level activity—pilgrims, wheels, immediate architectural context—while de-emphasizing vertical elements that would require taller formats to capture comprehensively.

Documenting active religious practice presents challenges distinct from photographing empty sacred spaces. Prayer wheel circumambulation generates continuous movement, changing light as sun crosses sky, unpredictable interactions between pilgrims, tourists, monks, vendors. The panoramic photo collage technique assembles multiple photographs into unified views, potentially representing the practice’s sequential nature through spatial distribution across horizontal width. Where single-frame photography freezes one moment, assembled panorama suggests temporal progression—successive moments of wheel spinning, different pilgrims at different stages, cumulative effect of many individual devotional acts within shared sacred geography.

The title’s use of “Prayer Wheel” singular rather than plural creates interpretive ambiguity. Does this focus on one particular wheel among hundreds circumscribing the stupa? Does it reference the prayer wheel concept generally while documenting many individual wheels? Or does the specificity suggest close documentation of wheel mechanics, iconography, devotional use—lateral scanning across surface details, construction methods, relationship between wheel and pilgrims spinning it, the width accommodating both detail and spatial context within unified view?

This represents the only Nepalese work in Hayashi’s Sacred Architectures series, created during the same 2004 campaign that produced Tamil Nadu temple documentation. Geographic expansion from India to Nepal demonstrates systematic coverage of Himalayan and South Asian Buddhist traditions: Japanese Buddhism, Tibetan exile institutions in India’s Dharamsala, now Tibetan Buddhism in Kathmandu Valley. UNESCO designated Boudhanath a World Heritage Site in 1979, recognizing it as “one of the most imposing symbols of Buddhism in Nepal” and emphasizing “living heritage” concept—acknowledging that cultural monuments’ value derives from continuous use within living traditions, not preservation as static artifacts. The Cleveland Museum of Art acquired this work in 2014, paired with Meenakshi Temple donation the same year, creating significant South Asian religious architecture presence in Hayashi’s home city museum. Remarkably, only one edition was ever printed—the Cleveland Museum’s framed copy—while remaining four editions exist only as packets, suggesting the work was created specifically for museum placement or printed only when that donation materialized.