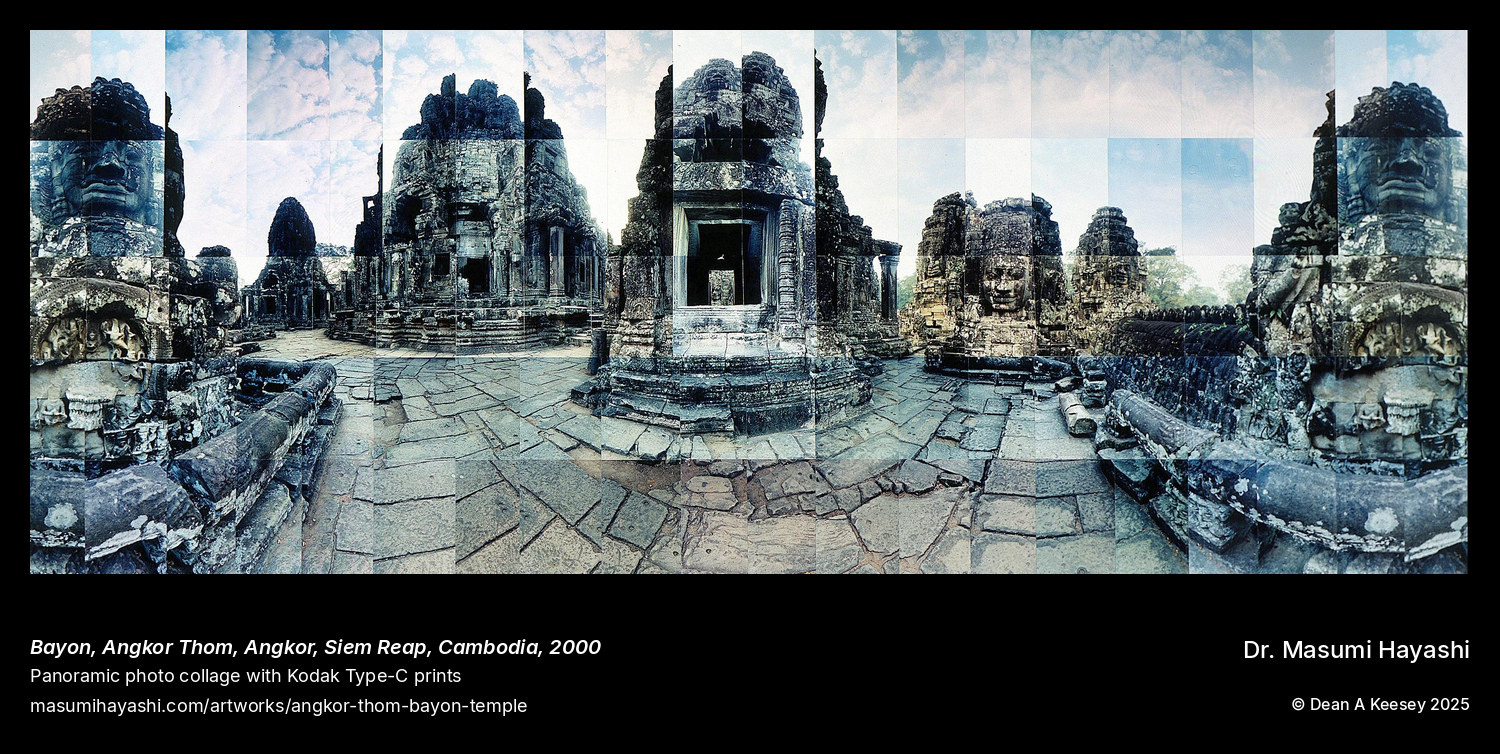

Bayon, Angkor Thom, Angkor, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Angkor, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Panoramic Photo Collage

2000

27 x 69

At the geometric center of Angkor Thom—the last great capital of the Khmer Empire—King Jayavarman VII built a temple where 216 massive stone faces stare outward from 54 towers, creating what might be the most unsettling architectural experience in Southeast Asia. Are these faces the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, whose name means “looking down” at the suffering world with compassion? Are they portraits of Jayavarman VII himself, the god-king gazing omnipresently over his kingdom? Scholarly consensus suggests synthesis: divine authority and earthly power merged through architectural symbolism so complete that asking whether these serene smiles belong to Buddha or monarch misses the theological point. In the late 12th century, when Jayavarman VII dramatically shifted Angkor from Hindu dominance to Mahayana Buddhism, the distinction collapsed.

What Hayashi captured in this extreme vertical panorama—27 by 69 inches, nearly six feet tall—is the vertiginous effect of standing beneath architecture where surveillance becomes theology. Each tower bears four faces oriented to cardinal directions. The math becomes overwhelming: 54 towers multiplied by four faces equals 216 giant visages, each approximately two meters high, with half-closed eyes that appear to track movement, broad noses, full lips, elongated earlobes signifying wisdom, elaborate crowns suggesting royalty or divinity. The “Khmer smile” or “smile of Angkor”—serene, knowing, inexplicably haunting—repeats across the upper terrace in rhythmic visual patterns that create what visitors since French colonial rediscovery have described as walking through a forest of stone giants who watch your every step.

The vertical format emphasizes what horizontal panoramas cannot capture: how these faces stack and ascend, how tower elevations create tiered galleries of stone regard, how the architecture organizes visual power through height. This matches the 69-inch vertical extent Hayashi used for the Bodhi Tree at Bodh Gaya, suggesting consistent format strategy for subjects requiring dramatic upward documentation. Here the composition likely isolates single tower elevations showing multiple face-levels from base to summit, or documents several towers’ vertical arrangement creating the repetitive rhythm of massive visages climbing toward sky. The narrowness of the format—just 27 inches wide—forces concentrated attention on vertical ascent, on accumulated visual weight of stacked stone faces gazing downward at the kingdom they were built to protect and govern.

Bayon marks revolutionary religious transformation. Where Angkor Wat’s bas-reliefs depicted Hindu mythology—the Ramayana, the Churning of the Ocean of Milk, battles between gods and demons—Bayon’s 1,200 meters of carved galleries document historical events. The south gallery preserves the famous Khmer-Cham naval battle on Tonlé Sap Lake, complete with ships, crocodiles, daily life vignettes. East galleries show royal processions and military marches. North galleries depict markets, cooking, festivals, games—invaluable documentation of 12th-13th century Khmer society rendered in stone. This represents Jayavarman VII’s ideological program: a Buddhism that engaged worldly suffering rather than transcending it, a royal cult that demonstrated power through architectural presence rather than purely mythological reference.

The king’s ambition stuns even by Angkorian standards. During his reign from 1181 to 1218 CE, Jayavarman VII built 102 hospitals throughout his kingdom, 121 rest houses along roads for travelers, plus major temple complexes including Ta Prohm (dedicated to his mother), Preah Khan (dedicated to his father), and this state temple that became the spiritual and geometric center of Angkor Thom’s nine square kilometers enclosed by walls and moats. The construction scale suggests labor mobilization that may have contributed to the empire’s eventual decline—you can build too much, even in stone, even when claiming divine authority.

By 2000, when Hayashi photographed these towers, Bayon had survived Cham invasion, French colonial “rediscovery,” Japanese occupation, American bombing campaigns, Khmer Rouge genocide, systematic looting. UNESCO’s 1992 World Heritage designation brought conservation funding and tourist crowds. The faces continue their surveillance, serene and knowing, watching over ruins that demonstrate how completely religious architecture can embody political theology. These aren’t decorative stone carvings. They’re arguments about omnipresence, about how divine compassion and royal power might manifest through identical stone smiles repeated 216 times across a temple complex that announced: we see everything, we know everything, and we smile because we understand that suffering and sovereignty emerge from the same cosmic source.