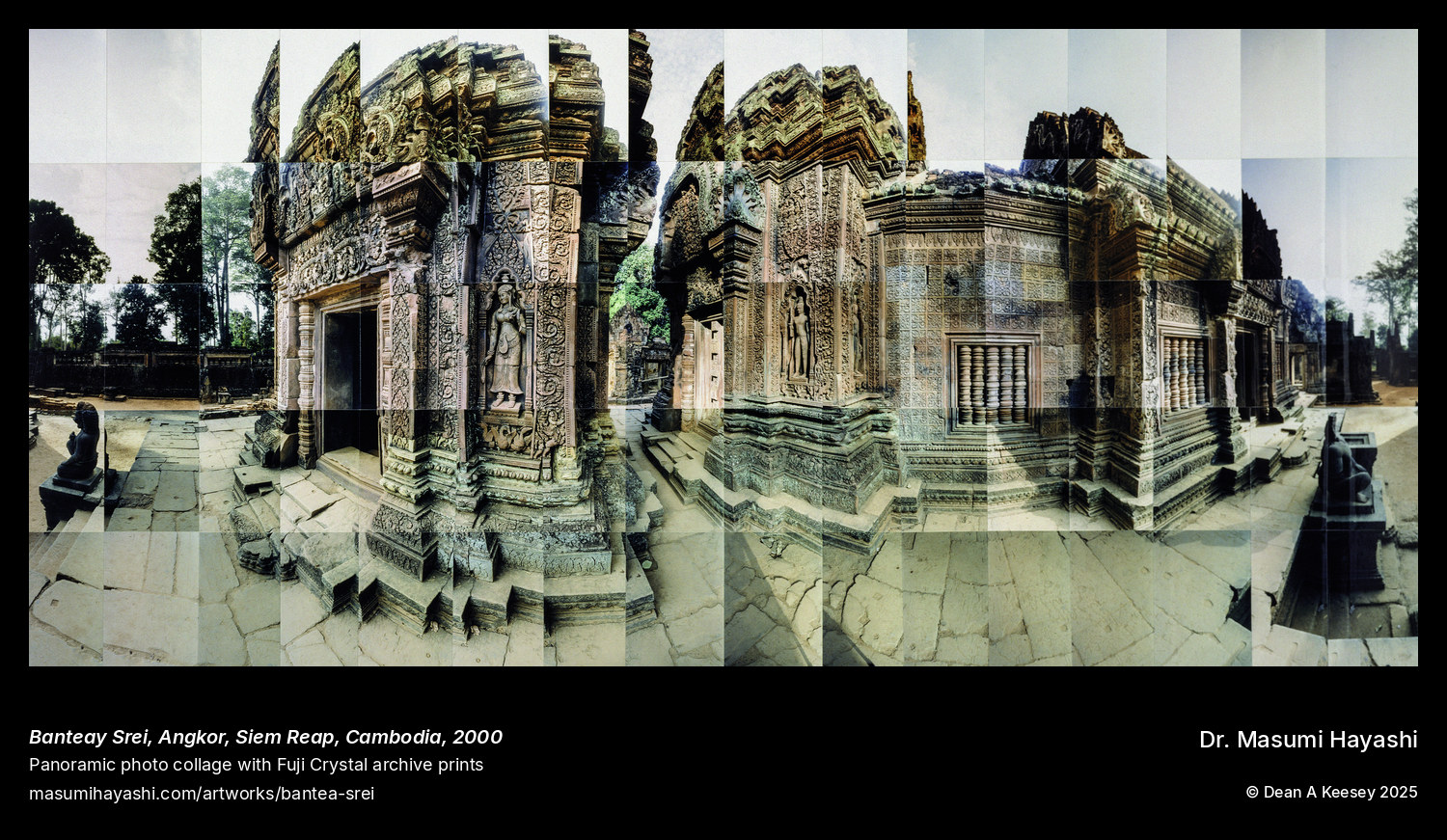

Banteay Srei, Angkor, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Angkor, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Panoramic Photo Collage

2000

27 x 56

Twenty-five kilometers northeast of Angkor Wat stands a 10th-century temple that art historians regard as the finest stone carving in Khmer civilization. Banteay Srei—“Citadel of Women”—earned its name either from the delicacy of its sculptural refinement or its dedication to goddess worship. The etymology remains unclear, but the exquisite detail carved into every surface tells an unambiguous story about what becomes possible when devotion meets pink sandstone soft enough to work like wood. In 2000, Hayashi documented what happens when architectural ambition prioritizes perfect detail over monumental scale, when a royal counselor rather than a king commissions a temple, when sculptors can undercut stone to create shadows that make doorways appear draped in lace rather than carved from rock.

The pink sandstone matters technically and aesthetically. Unlike the harder gray stone used for Angkor Wat and most major temples, this material from local quarries allowed sculptors in 967 CE to achieve three-dimensional relief impossible elsewhere in the Angkor complex. The pediments depict Ramayana episodes with such precision you can distinguish individual facial expressions on figures smaller than your hand. Ravana shakes Mount Kailash while Shiva sits unperturbed. Krishna battles demons across lintels covered in floral patterns that resemble jewelry more than geology. The dvarapalas—protective deities flanking doorways—wear elaborate costumes with visible textile folds, carry weapons with decorative detail, display individualized features despite repeated iconographic conventions. Nearly 2,000 apsaras dance across walls, each celestial figure unique in headdress and posture.

What makes Banteay Srei exceptional within Angkor’s architectural tradition is precisely its modest scale. This isn’t a cosmic mountain symbolizing divine geography. It’s three brick towers on a common platform, satellite libraries flanking a causeway, enclosure walls creating intimate rather than monumental space. The temple’s patron, Yajnavaraha, was a royal counselor and priest, not royalty—rare evidence that Khmer religious culture extended beyond strictly royal building programs. His Shaivite dedication to Tribhuvanamahesvara (a form of Shiva) reflects 10th-century Hindu dominance before Buddhist influences transformed Angkor’s religious landscape. Where Angkor Wat impresses through sheer scale and cosmic symbolism, Banteay Srei achieves sublimity through refinement, through sculptural detail so extraordinary that French art thieves including André Malraux attempted to steal carved apsaras in 1923, creating international scandal.

Hayashi shot this work on Fuji film rather than her typical Kodak stock, using 4x6 negatives instead of the standard 3.5x5 format. The choice suggests technical response to specific conditions—Fuji’s warmer color bias and enhanced red sensitivity likely better captured the pink sandstone’s distinctive hue. Color accuracy matters when documenting material whose aesthetic power depends on how rose-colored light interacts with carved surfaces. The larger negative format provided resolution necessary for capturing minute details that define Banteay Srei’s artistic achievement: the finger gestures on dancing figures, the ornamental patterns on guardian weapons, the fabric folds suggesting textile rather than stone.

All five editions of this work sold or found institutional homes. The Hayashi Foundation archive notes its absence with a single word: “Bummer!” That retrospective regret acknowledges strategic error. Complete edition placement means no examples remain available for exhibitions, loans to museums, research access for scholars studying Hayashi’s Angkor documentation, or future institutional placements. The success reveals market recognition—collectors familiar with Angkor understood Banteay Srei’s cultural significance, museums prioritizing Southeast Asian art valued documentation of what UNESCO designates world heritage. But it also demonstrates evolving curatorial wisdom. Later in her practice, Hayashi typically retained one to three editions of major works, understanding that immediate sales create future availability problems.

As a 2000 work, Banteay Srei predates Hayashi’s documented concentration on Indian temples (2003) and Nepal’s sacred sites (2004), suggesting her Asian sacred architecture project began with Southeast Asian documentation before expanding to South Asian Hindu-Buddhist traditions. This represents mid-career work—she was 55, six years before her death, at peak physical capacity for international travel and demanding photographic fieldwork. When she stood before these pink sandstone towers, she documented a truth about sacred architecture that monumental scale often obscures: sometimes devotion finds its most perfect expression not in moving ten million stone blocks to build cosmic mountains, but in carving a single lintel with such refined attention that stone becomes transparent to the mythological narratives it depicts, that architectural ornament achieves the status of scripture.