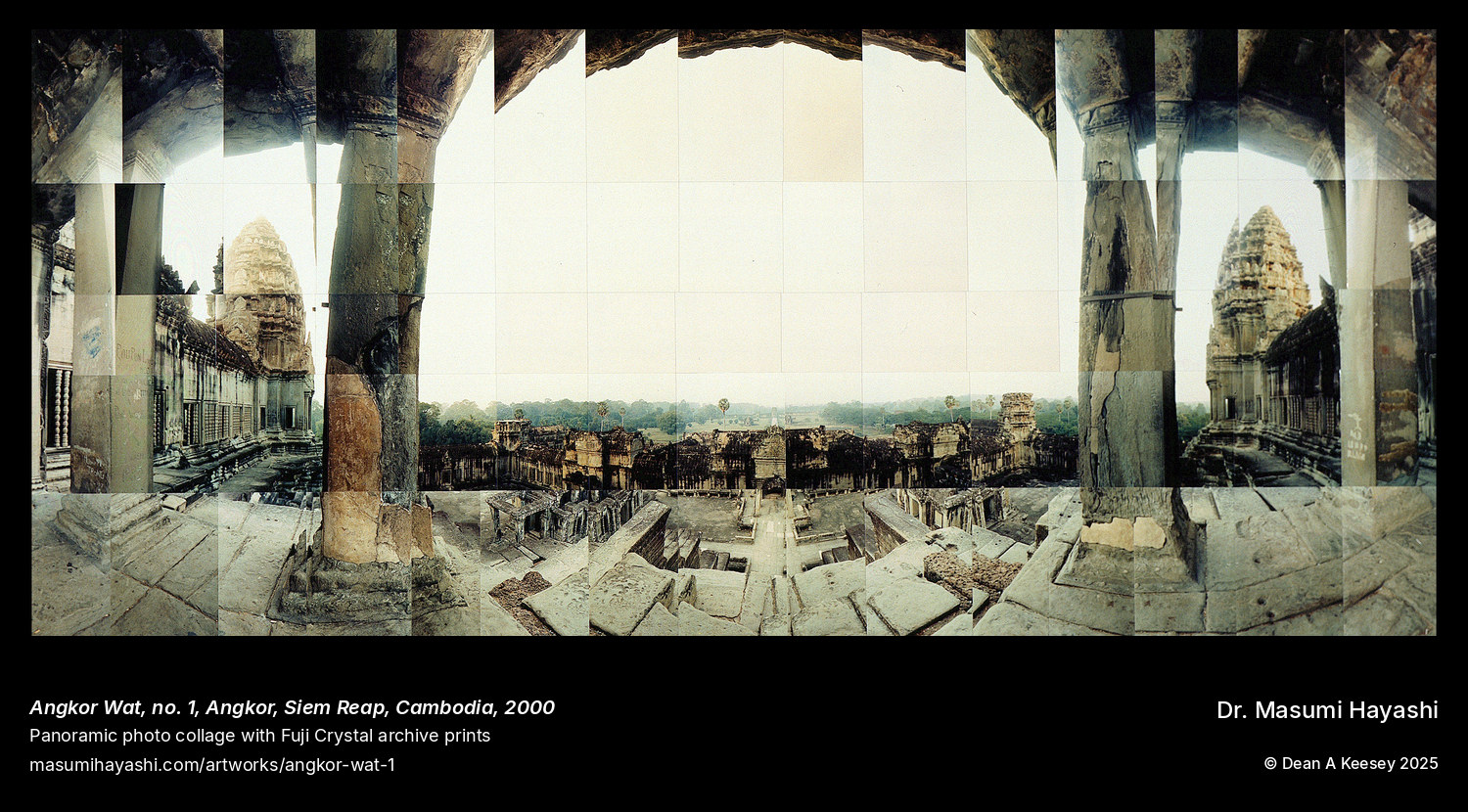

Angkor Wat, no. 1, Angkor, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Angkor, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Panoramic Photo Collage

2000

23 x 52

In the year 2000, Hayashi stood before the world’s largest religious monument with her panoramic camera, documenting what medieval Khmer architects understood about reaching toward heaven. The vertical format tells you everything: this is a work about ascent, about how stone towers can represent cosmic mountains where gods dwell. At 23 by 52 inches, the composition climbs from gallery platforms through graduated temple levels toward the central spire that rises 213 feet above the Cambodian jungle. This is Mount Meru rendered in sandstone—the diamond pattern of five towers built in the early 12th century during King Suryavarman II’s reign, when the Khmer Empire commanded Southeast Asia and could move ten million blocks of stone 25 miles from quarries to create architectural theology.

What fascinates is the religious fluidity embedded in these stones. Built as a Hindu shrine dedicated to Vishnu, the temple’s western orientation suggested funerary purposes, a royal mausoleum wrapped in 2,600 feet of bas-relief carvings depicting the Ramayana, the Churning of the Ocean of Milk, battles between gods and demons. Nearly 2,000 apsaras—celestial dancers—grace the walls with individual faces despite repetitive iconography. Yet by the 13th century, Cambodia had shifted toward Buddhism, and rather than abandon this architectural marvel, the culture absorbed it. Buddha images appeared in galleries designed for Hindu deities. The temple that symbolized Vishnu’s cosmic mountain became a Buddhist monastery without fundamental contradiction, because both traditions recognized sacred geography when they encountered it.

Hayashi’s narrow vertical panorama—the narrowest width at 23 inches among her significant vertical works—forces the eye upward through spatial hierarchies that medieval pilgrims experienced as spiritual progression. Ground-level galleries where bas-reliefs tell epic stories. Intermediate platforms with pillared halls marking transitional sacred zones. The upper terrace restricted to those who had ascended through progressive purification. Finally, the quincunx towers shaped like lotus buds, the central peak reaching toward sky that represents divine transcendence. The format isn’t documentation; it’s phenomenology. This is how it feels to stand beneath architecture designed to lift human consciousness from earthly concerns toward cosmic understanding.

The “No. 1” designation signals systematic coverage. Hayashi understood that monuments this complex require multiple works—different perspectives, compositional approaches, architectural elements isolated for study. This first Angkor Wat piece emphasizes tower elevation. Somewhere in her archive likely exists No. 2 documenting bas-relief galleries, perhaps No. 3 capturing the approaching causeway across the moat that represents the cosmic ocean. Major sites in her practice received serial treatment: two confirmed works at Hampi, multiple pieces exploring Meenakshi Temple’s labyrinthine architecture. Comprehensive documentation acknowledges that single images can’t contain centuries of devotion, architectural innovation, religious synthesis.

This stands as the fifth work from Hayashi’s 2000 journey across India and Cambodia—an extraordinary photographic pilgrimage documenting Buddhism at Bodh Gaya where the Buddha achieved enlightenment beneath the Bodhi Tree, Hinduism at Khajuraho’s tantric temples, Jainism at Jaisalmer’s merchant-patronized shrines, and Hindu-Buddhist synthesis here at Angkor. All five works employed identical Fuji 4x6 film specifications, suggesting methodical technical preparation for a journey designed to capture how South and Southeast Asian civilizations built theology into stone. This is sacred architecture as philosophical argument—the claim that human hands can construct spaces where the divine becomes tangible, where ascending stone staircases replicates the soul’s journey toward enlightenment or moksha or nirvana depending on which tradition interprets the climb.

By 2000, Angkor Wat had survived French colonial “rediscovery,” Japanese occupation, American bombing campaigns that cratered the surrounding jungle, the genocidal Khmer Rouge period, systematic looting of priceless sculpture for international art markets, landmines planted in defensive perimeters. UNESCO’s 1992 World Heritage designation brought conservation funding and tourist crowds that now threaten through sheer volume what violence couldn’t destroy. The temple appears on Cambodia’s national flag, a symbol of cultural continuity surviving apocalyptic rupture. When Hayashi photographed these towers, she documented resilience that transcends any single religious interpretation—the human need to build permanence from impermanence, to stack stones into arguments against mortality, to create spaces where ordinary consciousness might encounter something vast enough to be called sacred.