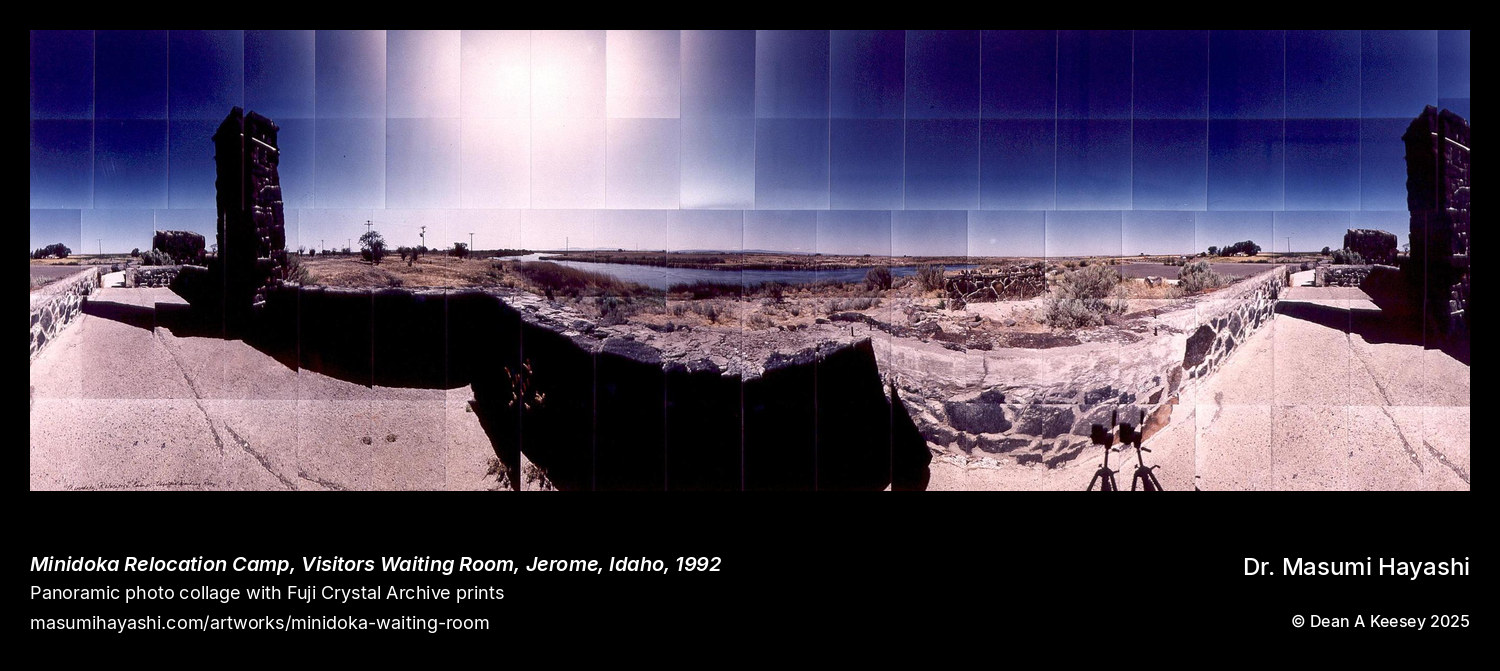

Minidoka Relocation Camp, Visitors Waiting Room

Jerome, ID, USA

Panoramic photo collage with Fuji Crystal Archive prints

1992

27 x 70

This monumental 27-by-70-inch horizontal panorama documents the visitors waiting room at Minidoka Relocation Center—one of the few remaining structures from the Idaho camp where 13,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned from 1942 to 1945. The nearly six-foot width captures the space where families separated by incarceration attempted to maintain connection under government surveillance.

Created in 1992, this represents one of Hayashi’s earliest camp documentations, predating her concentrated mid-1990s systematic coverage of all ten War Relocation Authority sites. The waiting room’s survival—while barracks, guard towers, and most administrative buildings disappeared—creates ironic memorial: a space designed to manage outside contact now serving as remnant of entire vanished camp city.

Minidoka’s location in Idaho’s high desert subjected internees to extreme temperatures, dust storms, and psychological isolation. The camp primarily held Japanese Americans from Seattle, Portland, and the Pacific Northwest—communities disrupted by forced removal, businesses forfeited, homes abandoned, with only what could be carried permitted in hastily packed luggage.

The visitors waiting room documents the bureaucratic management of family life under incarceration. Visitors (typically Caucasian spouses, employers, or friends of internees) required advance permission, scheduled appointments, and supervised meetings. The architecture of control transformed intimate relationships into administrative transactions.

The horizontal format captures the waiting room’s institutional character: standardized chairs, government-issue furniture, the aesthetic of processed humanity. The space’s neutral functionality masked its purpose within a system of constitutional violation, the waiting room serving as threshold between imprisoned community and outside world that continued normally while citizens remained confined.

Minidoka became a National Historic Site in 2001, the federal government formally acknowledging that sites of injustice warrant preservation alongside monuments celebrating achievement.